[As of April 2nd, 2013, one of the authors of The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus — Mike Licona — has acknowledged factual errors in the book’s section dealing with the 10/42 apologetic (pg. 128). I have revised the article in places to modify some of my criticisms in light of Licona’s respectful admission.]

[As of June 20th, 2013, I have just learned that apologist Cliffe Knechtle has acknowledged errors in the 10/42 apologetic. I apologize for not mentioning Cliffe’s admission sooner, since he appears to have written it in 2012, but I just now learned of it. In his reply, Cliffe asks me a series of questions about the historical reliability of the Gospels, to which I reply.]

[Other Christian apologists who have circulated the completely inaccurate 10/42 apologetic in print include: Norman Geisler and Frank Turek in I Don’t Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist (pg. 222), Dean Hardy in Stand Your Ground (pg. 115), Douglas Jacoby in Compelling Evidence for God and the Bible (pg. 132), Graeme Smith in Was the Tomb Empty? (pg. 98), H.R. Huntsman in Reason to Believe, Patrick Ford in Faith Isn’t Blind, and Jerry Newcombe in The Unstoppable Jesus Christ. An honorable mention likewise goes to Peter Eddington in “Was Jesus Really Resurrected?” in Christian magazine Beyond Today.]

[Mike Licona has also cited the 10/42 apologetic in The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach (pg. 590), but since Licona has acknowledged making errors with the same statistic in The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus (pg. 128), his statement about the sources for Tiberius versus Jesus in The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach (pg. 590) can be considered likewise conceded. Gary Habermas, the other co-author of the aforementioned book, also cites the 10/42 apologetic in Resurrected? (pg. 78).]

[Michael Wilkins and J.P. Moreland make an even more egregious generalization in Jesus Under Fire: Modern Scholarship Reinvents the Historical Jesus (pg. 215), where they state, “we need to realize that for the reign of Tiberius there are only four sources: Suetonius, Tacitus, Velleius Paterculus (a contemporary), and Dio Cassius.” The analysis below shows how there are 46 more literary sources than Wilkins and Moreland’s four main sources (in addition to hundreds more epigraphical and papyrological sources), meaning that Wilkins and Moreland emphasize less than 10% of the total literary sources for Tiberius. N.T. Wright has also stated in Jesus and the Victory of God, “It would be easier, frankly, to believe that Tiberius Caesar, Jesus’ contemporary, was a figment of the imagination than to believe that there was never such a person as Jesus.” Anyone may read the analysis below and decide whether Wright’s comparison is in proportion to the evidence.]

[Beyond the authors listed above, no less than six Christian publishing houses have either circulated the completely inaccurate 10/42 apologetic, or made similarly flawed comparisons between the historical evidence for Tiberius versus Jesus, including Kregel Publications, Crossway, Harvest House Publishers, Zondervan, Monarch Books, and InterVarsity Press, in addition to the Christian apologetics website CARM and Christian magazine Beyond Today. The simple fact that so many Christian publishers could independently circulate such an egregiously false comparison, without fact-checking it, speaks volumes to the quality of information in Christian apologetics.]

A couple of years ago I was having my annual argument with apologist Cliffe Knechtle when he visited the University of Arizona. Cliffe read some grand new “proof” of the “overwhelming historical evidence” for Jesus, claiming that 42 ancient sources record Jesus 150 years within his lifetime, whereas only 10 mention the contemporary Roman emperor Tiberius. Of course! Clearly more people knew about a Galilean rabbi in antiquity than their own emperor Tiberius! The bizarre argument, of course, immediately failed the smell test and I had no doubt that I was facing a skewed statistic. Nevertheless, the argument was of special interest to me: not only do I regularly engage in counter-apologetics, but also, as a Classics Ph.D. student, the reign of the emperor Tiberius is one of my areas of academic research.

I asked Cliffe to name the “10 sources” he had for Tiberius, he pulled a list out of his pocket (that I had no doubt he had copied from someone else), and read them out. Having personally studied the sources for Tiberius’ reign, I immediately noticed that a number of the authors I was familiar with were missing from the role call. Cliffe’s list was inaccurate and incomplete, but more importantly the source he copied it from was. As with most apologetic street debate venues, the audience did not have the time or background to fully investigate Cliffe’s claim before the topic changed to another question. So Cliffe merely bombarded the audience with a blown up statistic, expecting people to gullibly accept his claim and to not do their homework on the matter. Unfortunately for Cliffe, this blog about the statistic is that very homework.

Comparing the source material for Jesus to Tiberius does raise an interesting challenge: Let’s see just how much more we know about a well-documented historical figure like Tiberius Caesar compared to a highly obscure and historically inaccessible figure like Jesus of Galilee.

I searched the “10/42” number on Google and quickly came across a brief CARM (Christian Apologetics & Research Ministry) webpage written by Ryan Turner, which included the list of authors that Cliffe had copied:

Even Turner really does not deserve credit for the research on the CARM page, since half of the article was merely a direct quote out of Gary Habermas and Mike Licona’s The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus (pg. 128). Finally, after some muckraking I had dug up the original source coming from some big name apologists! Habermas is regarded as an “expert” on the resurrection of Jesus and Licona is his apprentice in the Dark Side. [Star Wars joke aside, I am grateful since then that Licona has since acknowledged the error.]

Ryan Turner’s article is titled “Did Jesus Ever Exist?” and he gives the 10/42 statistic as proof that “If one is going to doubt the existence of Jesus, one must also reject the existence of Tiberius Caesar.” This is a typical apologetic fallacy of false alternatives. Nevertheless, I will be clear from the beginning that, while there are a couple mythicist scholars and historicity agnostics that I do not regard as “radical skeptics” like Turner, I personally agree with the position that Jesus was more likely an obscure historical figure.

So what? As we will see, the sources for Jesus are so late, unreliable, and sparse that we can only roughly reconstruct anything reliable about his life. Nevertheless, the impression that Cliffe and Turner are trying to create by spouting grand numbers like “42 sources for Jesus, but only 10 for a famous emperor” is that the historical knowledge for Jesus is greater than that of other well-established historical figures. Taken to its extreme, it is a version of the wild claim: “We know more about Jesus than any other person from antiquity!” This statement, as we will see, is completely absurd (furthermore, if anyone, we know more about Marcus Tullius Cicero, who authored a massive Latin corpus that includes details of nearly every event in his life, than anyone else from antiquity, especially a most likely illiterate Galilean whom nobody even mentions until decades and centuries after his death).

I will provide TEN reasons why the 10/42 source comparison between Tiberius and Jesus is an inaccurate, skewed, and misleading statistic:

1. The 10/42 Is Misleading about the Literary Sources for Jesus

When Habermas and Licona list the 42 “accounts that now exist concerning Jesus” (The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus, pg. 233), they fail to specify that these are literary sources preserved through ancient narratives. Historians also consider epigraphical, papyrological, and numismatic evidence (all of which are far more abundant for Tiberius than Jesus), but we will cover that later. I only specify that these are “literary sources” to dispel the impression that these are the “only” sources.

Habermas and Licona first list the traditional authors of the New Testament:

“Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, Paul, Author of Hebrews, James, Peter, and Jude.”

What need only be said here is that all of the traditional attributions given above are doubted by most critical scholars, with the exception of Paul. Church leaders in the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE mis-attributed apostolic authorship to anonymous books like the Gospels (as I explain further in my article “Why Scholars Doubt the Traditional Authors of the Gospels”), a few works like Revelation were written by a “John” but not John the apostle, and some of the letters like 1st and 2nd Peter are outright forgeries (see NT scholar Bart Ehrman’s Forged: Writing in the Name of God). Once the false attributions are laid aside, there are no writings about Jesus that can be traced either to an original apostle or to an eyewitness. Paul is a near contemporary to Jesus’ life, however, he never saw or knew Jesus during his life and ministry. Moreover, Paul’s letters, while they deal with Jesus, are very sparse about the biographical details of his life and are primarily absorbed in theological concerns (see Ehrman’s article “Why Doesn’t Paul Say More About Jesus?”). For the limited biographical details about Jesus that I think the undisputed Pauline letters provide, see here.

Next, Habermas and Licona provide a list of supposedly “early” Christian writers:

“Clement of Rome, 2 Clement, Ignatius, Polycarp, Martyrdom of Polycarp, Didache, Barnabas, Shepherd of Hermas, Fragments of Papias, Justin Martyr, Aristides, Athenagoras, Theophilus of Antioch, Quadratus, Aristo of Pella, Melito of Sardis, Diognetus, Gospel of Peter, Apocalypse of Peter, and Epistula Apostolorum.”

A big number, but what Habermas and Licona fail to specify is that most of these authors’ writings date to the 2nd century CE (around a century after Jesus’ death). They are so late that they provide little independent information, and mostly make use of the above 1st century sources (or even less reliable later traditions). Playing telephone with previously problematic information does nothing to improve historical accuracy.

The next bit is a list of “heretical” authors who mention Jesus. I would prefer that Habermas and Licona use a more neutral term like “apocryphal.” Here are the four they give:

“Gospel of Thomas, Gospel of Truth, Apocryphon of John, and Treatise on Resurrection.”

Even apologists acknowledge that these sources are unreliable (though, modern scholars think that there may be a few historical sayings of Jesus in the Gospel of Thomas). Likewise these apocryphal sources, in many instances, contradict (the already internally contradictory) authors of the New Testament. More telephone, divergence, and “heretical” accounts does not improve the historical evidence.

So far we have only received a catalog of late Christian authors, which Habermas and Licona misleadingly represent as early, reliable sources. But Habermas and Licona’s next list of 9 “secular” sources for Jesus is highly questionable. To start with, the term “secular” is misleading, since these are really just “Pagan” authors (or in the case of Josephus, “Jewish”). But what is more noteworthy is that many of these authors never directly mention Jesus. Here is the list provided:

“Josephus (Jewish historian), Tacitus (Roman historian), Pliny the Younger (Roman politician), Phlegon (freed slave who wrote histories), Lucian (Greek satirist), Celsus (Roman philosopher), Mara Bar Serapion (prisoner awaiting execution), Suetonius, and Thallus.”

First off, Phlegon is an author who may have written in the 2nd century CE, most of whose works are lost. References to his lost works only survive in quotations of later authors, one of which is a quote from Julius Africanus (a lost 3rd century source), which itself is preserved in a second quote from the 9th century author Syncellus (that’s right, a quote of a quote seven centuries later!). After all this word of mouth Africanus claims that Phlegon wrote about the alleged three hour darkness at Jesus’ execution (described, or invented rather, in Mt. 27:45, Mk. 15:33, and Lk. 23:44). Phlegon’s quote, however, is preserved verbatim in Eusebius where no connection to Jesus is made, and instead Phlegon merely refers to an eclipse during Tiberius’ reign. There is another possible quote (unrelated to the eclipse) in Origen (Against Celsus 2.14) where Phlegon supposedly wrote about Jesus, but his words are not preserved verbatim, so it is difficult to ascertain. Regardless, Phlegon cannot be used as a source for the darkness at Jesus’ execution, and his verbatim quote about the unrelated eclipse may completely undermine Thallus as a source.

Thallus, like Phlegon, is a lost historian who only survives in later quotations and whose date is largely uncertain, but he probably wrote during the 2nd century CE. None of the later quotations of his works that include his own words mention Jesus. Instead another quote of Africanus, who does not record Thallus’ own words, claims that Thallus also wrote about the great darkness at Jesus’ execution, but once more this is only preserved by the 9th century author Syncellus. Given Africanus’ previous error, where he claimed that Phlegon wrote about Jesus, when his actual words did not, it is highly likely that Africanus misrepresented Thallus as well (there is also the possibility that Eusebius anonymously quotes Thallus in his Chronicle where no reference to Jesus is made in regard to the Tiberian eclipse). Lacking Thallus’ works or even a quotation of his own words that mentions Jesus, he cannot accurately be regarded as “an account that now exists concerning Jesus,” like Habermas and Licona claim, and thus including his name on the list is misleading.

For more information about how there is no outside corroboration of the darkness at Jesus’ execution, despite being an even that would have been documented worldwide, here is a valuable article from ancient historian Richard Carrier:

http://www.jgrchj.net/volume8/JGRChJ8-8_Carrier.pdf

Next, Mara Bar Serapion was a stoic philosopher whose dating has been disputed among scholars, but who may have written from the late-1st to the 3rd century CE (the latter of which dates would place him outside of the 150 year window). Serapion wrote a letter in Syriac that mentions in passing an anonymous “wise king of the Jews.” The letter does not refer to Jesus by name and can only be interpreted to allude to him. Nevertheless, some recent scholarship in the Mara Bar Serapion Project has favored a date in the late-1st century and has also favored the interpretation that the “wise king” is probably an allusion to Jesus. This conclusion would actually make Bar-Serapion the earliest Pagan to reference Jesus. However, the letter tells us nothing more than what is already known from the New Testament, namely that Jesus was a teacher who was executed (which Bar-Serapion compares with the killings of Pythagoras and Socrates). Furthermore, Bar-Serapion probably had no direct knowledge of Jesus, but instead only knew of him due to Christian preaching in Syria. As the Mara Bar Serapion Project explains, “Mara was not a crypto-Christian of the first century … Nor does the letter constitute an anti-Jewish Christian pseudepigraphon of the 3rd-4th century … More likely we are dealing with an early instance of the Pagan reaction to Christian preaching in Syria.” This means that Bar-Serapion is probably not an independent source for Jesus, and regardless his allusion is vague at best.

Suetonius’ passage cannot be said to refer to Jesus with any certainty. The only mention that might plausibly allude to Jesus is a two word ablative absolute in his Life of Claudius which states that, impulsore Chresto (“with a Chrestus instigating,” 25.4), the emperor Claudius banished Jews from Rome in 49 CE. “Chrestus” was not Jesus’ name, nor is it the Latin word for “Christ,” which is “Christus.” Likewise, “Chrestus” by itself is an attested name from antiquity meaning “good” or “useful.” Accordingly, it could very likely be the case that Suetonius’ reference to a “Chrestus” simply refers to the name of another Jew. Moreover, this refers to an event nearly two decades after Jesus was dead, even though the passage seems to imply that Chrestus was alive in 49 CE. As Classicist Barbara Levick (Claudius, pg. 122) concludes, “The precise cause of the expulsion remains obscure.” Suetonius also explicitly refers to Christianity as a religion later in his Life of Nero (16.2) without drawing any connection between the Christians and this “Chrestus.” Suetonius’ reference is thus far too dubious to be considered an “account” for Jesus, and thus it was rash to include it on the list.

Next we have Josephus from the late-1st century CE, who has one passage (AJ 20.9.1) that may refer to Jesus and his brother James, but has also been argued to refer to another Jesus (the Jewish high priest) and James, the sons of Damneus (which calls into dispute its supposed reference to the Christian Jesus). The more famous passage known as the Testimonium Flavianum (AJ 18.3.3) shows considerable signs of later forgery, making it either completely forged, or partially forged but still containing considerable alterations. Those qualifiers in place, it is fair to say that most scholars agree that Josephus probably preserves some reference to Jesus (and his brother James); however, since there is serious dispute about Josephus’ authenticity, he can only be regarded as a “disputed” source. Assuming that Josephus’ reference in the Testimonium Flavianum is partially authentic, Josephus discusses Jesus in the context of describing the “tribe of the Christians, so called after him” that “has still to this day not disappeared,” meaning that Josephus’ information about Jesus probably comes from Christians that he knew in his own day (calling into question Josephus’ status as an independent source).

Then there are Tacitus, Lucian, Pliny, and Celsus (all of whom are writing much, much later in the 2nd century CE). Pliny’s (Ep. 10.96-97) testimony can only dubiously be counted as an “account” for Jesus, since he only states that the Christians worship a “Christ” figure, as if a god, but does not connect this figure to a historical person. Josephus (if his partially or fully forged passage can be trusted), Tacitus (Ann. 15.44), and Lucian (The Passing of Peregrinus) only mention Jesus in the context of Christianity as a contemporary religious movement and furnish very few biographical details about his life. Celsus (the man for whom this blog is named) is a hilarious author whose lost work partially survives in quotations of the 3rd century theologian Origen. Celsus barely makes the 150 year window by writing c. 177 CE. His work The True Word is the earliest known comprehensive attack against Christianity, which includes hysterical remarks such as Jesus lying about his mother Mary’s virginity and actually being the bastard son of a Roman soldier named Pantera. It is a great read that I recommend for Monty Python: Life of Brian movie nights.

Well, there you have the so called “42 sources for Jesus,” a list that includes 3 disputed authors (Thallus, Suetonius, and Josephus), 2 indirect and vague allusions (Bar-Serapion and Pliny the Younger), and mostly records late authors who either furnish little to no reliable details about Jesus, or are problematic sources for interpretive reasons (such as the canonical Gospels). I will let the dubious references slide, since we will see that even with these embellishments Tiberius still has more than 42 sources! Paul is the only source that can be said to be a near contemporary of Jesus, but he provides only a few biographical details about Jesus to ascertain much that is substantial. Much of what I have refuted in this section should be known to many skeptics already; however, in the next section I am going to demonstrate how Habermas and Licona fail to accurately record the available sources for Tiberius.

2. The 10/42 Is Flatly Inaccurate about the Literary Sources for Tiberius, which Actually Comes Out to 49/42

Not only does this apologetic fail to mention all the authors who write about Tiberius 150 years within his lifetime, but it fails to mention nearly four-fifths of them! Here is the very incomplete list that is provided:

“Josephus, Tacitus, Suetonius, Seneca, Paterculus, Plutarch, Pliny the Elder, Strabo, Valerius Maximus, and Luke.”

It took me only a few minutes to track down authors that the apologetic had missed: The contemporary poet Horace (writing c. 21 BCE) mentions Tiberius multiple times and even writes to a military friend campaigning with Tiberius in the 3rd letter of book 1 of his Epistles. Another contemporary, Cornelius Nepos, also mentions Tiberius’ first marriage in his Life of Atticus (19). The poet Ovid (c. 13 CE) discusses Tiberius multiple times in book 2 of his Epistulae Ex Ponto. Livy’s history of Rome, though the books dealing with the time of Tiberius are lost, still have book summaries preserved in the later Periochae. A number of the later books, such as 138 dealing with Tiberius’ military campaigns under Augustus, provide yet another contemporary source for Tiberius. Likewise, another contemporary historian, Aufidius Bassus, wrote a history of the reign of Augustus down to his own day, which included the reign of Tiberius. While Bassus’ work is lost, a fragment remains that discusses Tiberius’ political achievements during the year 8 BCE, which was probably published during Tiberius’ lifetime. There is also Apollonides of Nicaea, a Greek grammarian from the early-1st century CE, whom the biographer Diogenes Laertius (9.12) records dedicated a work titled On the Silli to Tiberius. Since Apollonides probably dedicated this work during Tiberius’ reign, he is another source for Tiberius during his lifetime.

Habermas and Licona mention Seneca (presumably Seneca the Younger) on their list, but a reference survives to the contemporary Seneca the Elder’s (c. 38-39 CE) lost historical work in Suetonius’ Life of Tiberius (73.2), where the Elder Seneca writes about Tiberius’ death. Likewise, Philo of Alexandria (c. 39-40 CE) mentions Tiberius’s recent death multiple times in his Embassy to Gaius. These are both references that date to only a couple years after Tiberius’ death.

The list grows larger for later 1st century sources: The fabulist Phaedrus (c. 45 CE), who wrote Latin versions of Aesop’s fables, likewise writes a humorous tale about Tiberius and an attendant in his Aesopica. Scribonius Largus (c. 47 CE) writes about Tiberius in his Compositions (97.1), as does Columella (c. 65 CE) in book 11 of his De Re Rustica. A very obscure source for Tiberius that survives is a certain “Deculo,” whom Pliny the Elder (HN 35.70) records wrote about a painting that Tiberius hung in his bedroom, which cost 600,000 sesterces. Nothing is known of this Deculo outside of Pliny’s writings, but since the Elder Pliny died in 79 CE, Deculo must have written sometime in the 1st century CE. Quintilian (95 CE) also writes about Tiberius in book 3 of his Institutio Oratoria, and Frontinus (c. 100 CE) makes an obscure, but nevertheless solid reference to Tiberius in book 1 of his On the Water Supply of Rome.

Authors from the 2nd century CE are also missing from Habermas and Licona’s role call: the Roman satirist Juvenal (c. 120 CE) mentions Tiberius’ praetorian prefect Sejanus and a “Caesar on Capri” that indisputably refers to Tiberius in book 10 of his Satires. Likewise, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (c. 167 CE) is missing who briefly mentions Tiberius in book 12 of his Meditations. Vettius Valens (c. 175 CE) also records astrological details about Tiberius’ reign in book 1 of his Anthology. Cornelius Fronto (c. 175 CE) likewise mentions the library in Tiberius’ palace in book 4 of his Epistles, and the grammarian Aulus Gellius also mentions Tiberius’ library in book 13 of his Attic Nights (horribly obscure references, but they still include Tiberius’ name!).

Habermas and Licona include the Gospel of Luke in their list, since it refers to the 15th year of Tiberius Caesar’s reign as the beginning of John the Baptist’s ministry (3:1). However, apparently Habermas and Licona only counted his praenomen “Tiberius.” Tiberius had also received the adopted cognomen “Caesar.” Who is the Gospel of John referring to when the Jews cry, “We have no king but Caesar!” (19:15)? Whose face is on the coin when Mark and Matthew write, “render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s” (Mk. 12:17; Mt. 22:21)? If Pliny’s vague reference to a “Christ,” which was never Jesus’ name but only a title, can be counted as an “account” for Jesus, then surely these references to a “Caesar,” which is part of Tiberius’ name and also a title used to refer to the Roman emperor, can at least count as vague sources for Tiberius. Therefore, the other Gospels — Matthew, Mark, and John — also count as texts that allude to Tiberius within 150 years of his life and ones whom Habermas and Licona fail to record.

There are a number of authors that this apologetic counts for Jesus, but fails to mention also wrote about Tiberius! The apologetic counts Pliny the Younger’s vague reference to a “Christ,” but fails to mention that the Younger Pliny clearly discusses Tiberius in book 5 of his Epistles in his letter to Titius Aristo. Lucian is listed as a source for Jesus, but it is ignored that the Macrobii (“Long Lives”), which is attributed to Lucian, also mentions Tiberius. Although modern scholars now doubt that Lucian was the actual author of the Macrobii, there are still good reasons to think that this text preserves a 2nd century reference to Tiberius. Not only does the text make no reference to events after the 2nd century CE, but likewise the text makes no reference to the death of the philosopher Demonax (c. 170 CE), who allegedly lived about a hundred years, which would be very odd for a work dedicated to discussing people who lived very long lives. This provides adequate enough grounds for dating the Macrobii to before 170 CE, which puts it within the 150 year window.

The apologetic even misses important Christian sources that mention Tiberius. Justin the Martyr is counted for Jesus, but it is not pointed out that he also mentions Tiberius in his First Apology. Likewise, Theophilus of Antioch is counted for Jesus, but his reference to Tiberius in book 3 of To Autolycus is not included. The apologetic even fails to connect the dots when Phlegon and Thallus are counted as sources for Jesus, because they mention an eclipse during the reign of Tiberius, that these references include Tiberius Caesar! So the apologetic is not even checking its own sources! Phlegon likewise records in book 13 of his On Marvels that Apollonius the Grammarian wrote about Tiberius, which is also not included.

What about Tiberius himself? Unlike Jesus, Tiberius was indisputably literate and a number of his letters are preserved in fragments within the works of both Tacitus and Suetonius. In addition, Suetonius even makes clear in his Life of Tiberius that Tiberius wrote memoirs that he used when constructing his biography (61.1). Thus, Tiberius himself also counts as a source for his own life and existence. How about Tiberius’ stepfather Augustus? Suetonius likewise quotes a number of letters written by Augustus addressed to Tiberius, which likewise count as sources for Tiberius’ life. Furthermore, the historian Tacitus (Ann. 4.53) preserves a fragment of the memoirs of Agrippina the Younger, Tiberius’ great-niece, where she also relates information about Tiberius. A speech of Tiberius’ nephew, the emperor Claudius, is likewise preserved on the bronze Lyon Tablet that mentions Tiberius. Thus, within Tiberius’ own family we have Augustus, Claudius, and Agrippina the Younger as sources for him, in addition to Tiberius himself.

Another source is the Latin astrologer Manilius (c. 14 CE) who dedicated his poem the Astronomica to a “Caesar,” which could refer to either Tiberius or Augustus. Even if it is Tiberius’ adopted father Augustus, imagine how ecstatic apologists would be if a poem survived dedicated to Jesus’ adopted father Joseph! Beyond the dedication, most scholars agree that there is a reference to Tiberius in book 4, lines 764-6 of the Astronomica, as well as references to Tiberius’ horoscope.

There are a couple references to Tiberius that are dubious, but still provide plausible sources for his life. One source is a little known poem titled the Aratus, which is attributed to Tiberius’ nephew and adopted son Germanicus. Since the poem is dedicated to the author’s genitor (“father” or “adopted father”), if the attribution to Germanicus is correct, then this poem is a contemporary source dedicated to Tiberius. There is also a possible fragment of the Roman historian M. Servilius Nonianus preserved, which discusses an incident during Tiberius’ reign. Since Nonianus died in 59 CE, this would be another source for Tiberius within 25 years of the emperor’s life. There is also the Greek geographer Pausanias (c. 170 CE) who mentions in book 8 of his Descriptions of Greece that a “Roman emperor” constructed a channel near Antioch, whom scholars speculate was probably Tiberius. This reference is not 100% solid, but Tiberius was a “Roman emperor,” which is a more literal description than Mara Bar-Serapion’s “wise king of the Jews” being taken as a reference to Jesus, as Jesus was never a king.

Apart from these literary examples, at least three very extensive inscriptions survive. These inscriptions (much larger than other smaller inscriptions from the same period) are extensive enough to be considered their own narratives, in that they not only contain complete paragraphs, sentences, and clauses, but also have distinct openings and closings of narration. In content, they thus preserve as much information on stone as medieval codices preserve in writing (in addition to not having to rely on medieval textual transmission). The Res Gestae and the Senatus Consultum de Cn. Pisone were both published during the reign of Tiberius and refer to Tiberius specifically, and the Lex de Imperio Vespasiani, which was produced c. 69-70 CE, likewise refers to the powers that had been bequeathed to Tiberius by the Senate. The Senatus Consultum, written in the name of the Senate, even includes a smaller subsection that was written specifically by Tiberius’ sua manu (“own hand”). Apologists would kill for such extensive inscriptions to be recorded about Jesus during his lifetime (and would probably mention them in their statistic if they had existed), but yet Habermas and Licona fail to include these important sources for Tiberius.

Since Augustus is the putative author of the Res Gestae (even though it was published after his lifetime), and since Augustus’ letters to Tiberius are listed above, it may be double-counting to include the Res Gestae as an additional source; however, the Senatus Consultum de Cn. Pisone and the Lex de Imperio Vespasiani are definitely additional sources that should be included in this list.

All totaled, Habermas and Licona missed approximately 39 sources for Tiberius within 150 years of his life:

Horace, Ovid, Cornelius Nepos, Livy, Aufidius Bassus, Apollonides of Nicaea, Seneca the Elder, Philo of Alexandria, Phaedrus, Columella, Scribonius Largus, Deculo, Quintilian, Frontinus, Juvenal, Marcus Aurelius, Vettius Valens, Cornelius Fronto, Aulus Gellius, the Gospels attributed to Matthew, Mark, and John, Pliny the Younger, pseudo-Lucian, Justin the Martyr, Theophilus of Antioch, Phlegon, Thallus, Apollonius the Grammarian, Tiberius himself, Augustus, Germanicus, Claudius, Agrippina the Younger, Manilius, M. Servilius Nonianus, Pausanias, the Senatus Consultum de Cn. Pisone, and the Lex de Imperio Vespasiani

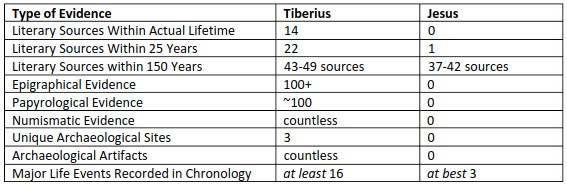

These are all of the additional sources that I have been able to find for Tiberius, but it should be noted that there may be even more sources that I have missed. I noted above that there are 3 disputed sources (Thallus, Suetonius, and Josephus) and 2 vague sources (Bar-Serapion and Pliny the Younger) for Jesus. To be consistent, the same consideration for Tiberius should apply, as there are 3 disputable sources (Germanicus, Servilius Nonianus, and Pausanias) and 3 vague sources (the Gospels attributed to Mark, Matthew, and John) for Tiberius. This brings the total tally for Jesus to 37-42 and for Tiberius to 43-49.

If one drops the 6 disputable or vague sources for Tiberius within 150 years of his life, this apologetic still only manages to account for 10 out of 43 of the total literary sources. That is an accuracy rate of only 23%. It should also be noted that even the low estimate of sources for Tiberius is still greater than the high estimate for Jesus. So, even with literary sources alone, Tiberius still wins!

3. The 10/42 Stretches the Window of Time to Skew the Results

One hundred and fifty years is a long time. Has anyone started to wonder at this point: why did Habermas and Licona choose such a large time span as 150 years for the window of authors? Would I writing this year (2012 CE) count as an independent “source” for Abraham Lincoln (1865 CE), just because I am within a 150 years of his life? The large window of time skews the results. Tiberius was a well-known politician in his own day, but as time goes on people forget old politicians in place of new ones. In contrast, Jesus became a religious figure who was revered and immortalized by a world religion. Consider an analogy with Joseph Smith. Most of us today are familiar with Joseph Smith over 150 years after his death, but how many are familiar with his contemporary U.S. president John Tyler?

That being said, historians prefer early, eyewitness, and contemporary sources to later, second-hand, and dubious ones. Let’s readjust our window of time. How many authors mention Tiberius during his actual lifetime (42 BCE — 37 CE) compared to how many mention Jesus during his lifetime (c. 7 BCE-7 CE — 26-36 CE)? When you readjust the numbers to actual contemporary authors, there are at least 14 accounts that record Tiberius during his actual lifetime:

Horace, Ovid, Cornelius Nepos, Livy, Aufidius Bassus, Apollonides of Nicaea, Strabo, Vallerius Maximus, Paterculus, Tiberius himself, Augustus, Germanicus, Manilius, and the Senatus Consultum de Cn. Pisone

Many of these are direct eyewitnesses, and Paterculus is an actual historian who fought under Tiberius and records his life and military campaigns at length. In contrast, what is the number of contemporary authors who mention Jesus? Absolutely zero. That’s right, when you readjust the number to actual contemporaries, it comes out to a 14/0 ratio in favor of Tiberius. So, skeptics, whenever you hear an apologist spout the “10/42” slogan, first remind them that the real number is 49/42, then remind them that the number for actual contemporaries is 14/0.

What about if we expand the window to near contemporaries? Say authors who wrote within 25 years of Tiberius and Jesus’ lifetime? For Tiberius, this adds:

Seneca the Elder, Philo of Alexandria, Seneca the Younger, Phaedrus, Scribonius Largus, Servilius Nonianus, Claudius, and Agrippina the Younger

For Jesus, this adds:

The Apostle Paul

Therefore, even for near contemporaries, the ratio comes out to 22/1 in favor of Tiberius, with Jesus being left with only one source, who is not an eyewitness. Overwhelmingly, there is an abundance of either contemporary or early reliable sources for Tiberius, whereas Jesus has no contemporary sources and very little early attestation. Readjusting the window of time puts in perspective just how strong the source material is for Tiberius and how weak it is for Jesus.

It also never occurs to Cliffe, Turner, Habermas, or Licona to ask why so many late sources for Jesus survive. Was there really more written about Jesus later in antiquity than Tiberius? Hardly. What really has happened is that more sources for Jesus were preserved through the Christian-dominated Middle Ages. As Reynolds and Wilson, authors of Scribes & Scholars (pg. 79), explain about medieval textual transmission, “Education and the care of books were rapidly passing into the hands of the Church, and the Christians of this period had little time for Pagan literature.” And likewise Reynolds and Wilson (pg. 48) point out, “There can be little doubt that one of the major reasons for the loss of classical texts is that most Christians were not interested in reading them, and hence not enough new copies of the texts were made to ensure their survival in an age of war and destruction.” Accordingly, the only reason why more texts mentioning Tiberius have not been preserved is because of a sample bias and a bottleneck of Pagan texts that perished during the Middle Ages. Despite this, an overwhelmingly larger number of early sources survive for Tiberius compared to a mere paucity for Jesus, and, even in the stretched out 150 year window, Tiberius is still more attested.

4. The 10/42 Ignores Epigraphical Evidence

Up until now I have been primarily focused on Habermas and Licona’s list of authors. I think it is safe to say at this point that their number has been utterly discredited. But let’s look further into Turner’s claim: “If one is going to doubt the existence of Jesus, one must also reject the existence of Tiberius Caesar.” Let’s consider some other types of historical evidence besides literary sources and see how much we would know about Tiberius even if all his literary sources disappeared.

Epigraphy is the study of ancient inscriptions in stone. I have already mentioned Claudius’ Lyon Tablet, the Res Gestae (seen below), the Senatus Consultum de Cn. Pisone, and the Lex de Imperio Vespasiani, which are inscriptions long enough to be considered their own narratives. However, there are countless other contemporary inscriptions that name Tiberius on dedications, plaques, and really more locations than I could ever possibly name. Current databases and collections for Greek and Latin inscriptions are incomplete and often difficult to access, but I ran a search for Latin inscriptions that include “Tiberius Caesar” on Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss, which yielded 152 results. The vast majority of these inscriptions refer to the emperor Tiberius (I think I saw one that referred to his grandson Tiberius Gemellus) and date to within his reign and lifetime. Mind you, this is just the tip of the iceberg! This is not even a search that includes Greek inscriptions and there are other prosopographies, such as Victor Erenberg’s Documents Illustrating the Reigns of Augustus & Tiberius, which include even more documentary sources.

To my knowledge, there is not a single inscription that mentions Jesus during his lifetime. In epigraphy, the ratio that would come out for Tiberius versus Jesus would be well above the realm of 100+/0.

5. The 10/42 Ignores Papyrological Evidence

I have already mentioned that the literary sources we have from antiquity come down primarily in medieval manuscripts. However, in more arid regions of the Mediterranean (particularly southern Egypt) documents from antiquity itself survive written on papyri. Papyrology is the study of such documents. I see no reason why texts preserved in medieval manuscripts should count as sources in Habermas and Licona’s statistic but papyrological sources should not.

Most papyri are rough drafts of letters, scrap notes, receipts, accounting documents, and other incidentals. Nevertheless, as we previously saw in the Gospel of Luke, the conventional method of dating in antiquity was to list the year of the current emperor’s reign. Accordingly, many of the papyri that include dates mention Tiberius’ name. I ran a search on APIS (Advanced Papyrological Information System) for papyri dating to the years of Tiberius’ reign (14 CE – 37 CE) that include the name “Tiberius.” The search yielded 106 results. (The link has since broken, but here is a PDF of a recent search I did.) The vast majority of these papyrological references refer to the emperor Tiberius (granted, a few refer to other people named Tiberius). In fact, one of these papyri (seen below) may plausibly be a letter from Tiberius himself to Egyptian tax collectors.

Other valuable papyri about Tiberius can be found with even simple Google searches: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Papyrus_Oxyrhynchus_240.

To my knowledge there is not a single papyrus dating to Jesus’ lifetime that mentions him. Granted, we do have historically unreliable papyri that mention Jesus centuries later (which also include a lot of apocryphal gems, such as Jesus having a twin brother). However, if we compare the ratio of solely contemporary papyrological sources it is ~100/0 in favor of Tiberius versus Jesus.

6. The 10/42 Ignores Numismatic Evidence

Numismatics is the study of ancient currency. During the Roman Empire, ancient coins were minted with the emperor’s name and face on them. Accordingly, there are countless coins (like the one below, dating to a period during Tiberius’ reign c. 16 CE – 22 CE) scattered throughout the Mediterranean that mention Tiberius’ name and brandish his face.

Now, to be fair, I would not expect an obscure Galilean like Jesus to have coins minted of himself (granted Alexander of Abonoteichus, another ancient prophetic figure living c. 105-170 CE, managed to pull it off for the snake-god of his cult). That being said, I only bring this up to address Turner’s claim: “If one is going to doubt the existence of Jesus, one must also reject the existence of Tiberius Caesar.” If all other forms of evidence suddenly vanished and we were only left with ancient currency, we would still have contemporary evidence for Tiberius and none for Jesus. One more point for Tiberius.

7. The 10/42 Ignores Archaeological Evidence

There are a number of archaeological sites around the Mediterranean that can be directly and reliably linked to Tiberius. Fortunately, I personally have had the opportunity to visit all of the ones below. There is Tiberius’ palace in the Roman forum (left), his villa at Sperlonga (middle), and one of his villas on Capri (right). Capri is the island featured at the top of this blog!

Now, there are a number of traditional sites attributed to Jesus, but virtually all of these are just later fabrications. For example, Jesus has two locations in Jerusalem that are supposed to be his empty tomb: the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and the Garden Tomb (both of which I visited this past summer). However, I am not aware of any archaeological site that can be directly connected to Jesus. That being said, Jesus is recorded to have visited general locations like the Mount of Olives and the Temple Mount, which is certainly plausible. I do not claim that this is the strongest argument, but there are archaeological sites we can specifically connect with Tiberius but none for Jesus. So at the end of the day it is just another way that we know more about Tiberius than Jesus.

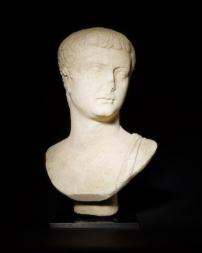

We also have artifacts that can be linked to Tiberius, such as the bust of his face below, which dates to within his lifetime (c. 10 CE – 30 CE). We have no such image for Jesus, nor do we even have a physical description of what he looks like. Admittedly, the countless statues we now have of Tiberius were idealized and are not fully accurate portraits, and simply because no physical description or image of Jesus exists does not prove his non-existence, but this is just yet another way we have more information about Tiberius than Jesus.

8. Not All Historical Sources Are Equal

A point that should not be forgotten in stacking all these numbers is that not all pieces of evidence are equal. Merely providing lists of authors, like Habermas and Licona did, creates the illusion that all sources are equal. But would one expect 100 issues of the National Enquirer to be more reliable than a single history book? We have already seen that many of the sources for Tiberius were written either during or much closer to his life, whereas Jesus’ are distant second, third, and fourth generation accounts.

But beyond this, we also have more reliable sources for Tiberius that provide much more historical information about his life than what is available Jesus. Paterculus is a contemporary, eyewitness historian who records Tiberius’ military campaigns, Tacitus has 6 books in his Annals that document Tiberius’ reign on a chronological basis, and Suetonius wrote a historical biography of him. In contrast, no contemporary historian documents Jesus and the much later historians who do mention him only do so in tiny quips that furnish little to no details about his life. Instead, our primary source material for Jesus is Paul’s Epistles, which mostly treat with theology rather than history (though they do include a few biographical details about Jesus), and the Gospels, which are ahistorical hagiographies comprised of symbolism, legends, and exaggeration. To sum it up, we have earlier, fuller, and more reliable historical sources for Tiberius, whereas for Jesus we have late, ahistorical, and unreliable religious texts.

9. Chronologically, Whose Life Can We Reconstruct Better: Tiberius or Jesus?

To provide an illustration of just how much more we know about Tiberius than Jesus, I thought it would be helpful to map out their lives in a chronology. After all, if we have a lot of historical information, shouldn’t we be able to plot it out on a timeline?

For the chronology of Jesus, there are considerable problems in assigning any precise dates or years to events in his life. To begin with, the Gospel of Matthew places Jesus’ birth before the death of King Herod in 4 BCE, but Luke states that Jesus was born during the Census of Quirinius, which took place in 6/7 CE. As historian E.P. Sanders (The Historical Figure of Jesus, pg. 87) explains:

“Possibly because there were riots after Herod’s death in 4 BCE and also at the time of the census in 6 CE, Luke has conflated the two times. This a relatively slight historical error for an ancient author who worked without archives, or even a standard calendar, and who wrote about a period some eighty or so years earlier. The most likely explanation of Luke’s account is this: he or his source accidentally combined 4 BCE (Herod’s death) and 6 CE (Quirinius’ census); having ‘discovered’ the event so that it became a reason for Joseph to travel from his home in Nazareth to Bethlehem. In any case, Luke’s real source for the view that Jesus was born in Bethlehem was certainly the conviction that Jesus fulfilled a hope that someday a descendant of David would arise to save Israel.”

Sanders’ last point about the expectation that the Jewish Messiah would be born in Bethlehem is likewise noteworthy. It is very clear that both Matthew and Luke’s accounts of Jesus’ birth were influenced by their narrative goals of depicting Jesus as a descendant of King David. As Sanders (pg. 88) elaborates:

“The birth narratives constitute an extreme case. Matthew and Luke used them to place Jesus in salvation history. It seems that they had very little historical information about Jesus’ birth (historical in our sense), and so they went to one of their other sources, Jewish scripture. There is no other substantial part of the gospels that depends so heavily on the theory that information about David and Moses may simply be transferred to the story of Jesus.”

These problems only allow for broad date ranges in estimating the year of Jesus’ birth (for a refutation of apologetic attempts to harmonize the nativity stories between Matthew and Luke, see Carrier’s “The Date of the Nativity in Luke”). On a wide range, the Gospels place Jesus’ birth anywhere from a couple years before Herod’s death (7-4 BCE) to the Census of Quirinius (6/7 CE). However, scholars have also favored a more narrow range of dates between these broader reference points. As Sanders (pg. 11) explains:

“Most scholars, I among them, think that the decisive fact is that Matthew dates Jesus’ birth at about the time Herod the Great died. This was in the year 4 BCE, and so Jesus born in that year or shortly before it; some scholars prefer 5, 6, or even 7 BCE.”

This allows for a narrow range of dating Jesus’ birth between 7-4 BCE. Dating the beginning of Jesus’ ministry is likewise problematic. Luke (3:1) states that John the Baptist began his ministry in the 15th year of the reign of Tiberius (29 CE), and implies that Jesus began his ministry not long after (29-30 CE). However, Sanders (pg. 282) cautions:

“This, however, is only an estimate. Luke did not write that Jesus started precisely one year after John. Moreover, we do not know how long Jesus’ ministry lasted. Consequently, Luke’s information cannot tell us when Jesus died.”

Dating Jesus’ death raises further problems. As with Jesus’ birth, both broad and narrow estimates can be provided. Regarding broad estimation, Sanders (pg. 54) notes:

“When Jesus was executed, Pontius Pilate was prefect of Judea (26-36 CE) and Caiaphas was high priest (18-36 CE) … These dates lead to the conclusion that Jesus died between 26 to 36 CE. This broad range is based on ‘big pieces’ of information. Tiberius, Pilate, and Caiaphas: everybody in Palestine knew those three names and during what period of time they held their respective offices.”

So, in a broad sense, Jesus’ death can be placed between the years 26-36 CE. However, it is fair to say that most scholars have favored a narrower range between these dates. Sanders (pg. 283) concludes:

“Taking into account Luke’s dating of the beginning of John the Baptist’s ministry, the period of Pilate’s administration, and the evidence derived from the chronology of Paul, most scholars are content to say that Jesus was executed sometime between 29 and 33 CE.”

With the cumulative analysis discussed above, the “broad range” of Jesus’ chronology may be calculated as follows:

Broad Chronology of Jesus: 7-4 BCE — 6-7 CE: Jesus is born 29-30 CE: Jesus begins his ministry 26-36 CE: Jesus is crucifiedFrom this wider estimate, scholars have tended to favor a more “narrow range” of chronology with the following years:

Narrow Chronology of Jesus: 7-4 BCE: Jesus is born 29-30 CE: Jesus begins his ministry 29-33 CE: Jesus is crucifiedIn contrast, with Tiberius we have reliable and precise historical sources that furnish not only accurate years, but even specific days! In fact, the amount of information we can know about, such as when Tiberius assumed specific offices, visited various provinces, and other precise details, is so abundant that I had to cut out a lot of material from his chronology. It should also be noted that, unlike in the case for Jesus, there is no serious scholarly dispute about these dates, making them even more authoritative. Here is a greatly abridged chronology taken from Robin Seager’s Tiberius (xiii – xvi):

Chronology of Tiberius: November 16th, 42 BCE: Tiberius is born 40 BCE: The infant Tiberius escapes the siege of Perusia 33 BCE: Tiberius’ father dies 27 BCE: Tiberius assumes the toga virilis 20 BCE: Tiberius marries Vipsania 11 BCE: Tiberius divorces Vipsania 12 BCE: Tiberius marries Julia 6 BCE — 2 CE: Tiberius’ retirement at Rhodes 4 CE: Tiberius is adopted by Augustus September 17, 14 CE: Tiberius assumes the principate 19 CE: Death of Tiberius’ nephew and heir Germanicus 23 CE: Death of Tiberius’ son Drusus 27 CE: Tiberius retires to Capri 29 CE: Death of Tiberius’ mother Livia October 18th, 31 CE: Tiberius executes his praetorian prefect Sejanus March 16th, 37 CE: Tiberius diesThe contrast between these charts is drastic. For Jesus the few events we can even plot require broad date ranges, whereas for Tiberius we have not only a reliable year-by-year breakdown but even specific dates. Tiberius’ whole life is well documented in ancient sources and accessible chronologically, whereas Jesus’ is buried in obscurity. The charts above speak for themselves on just how much more we know about Tiberius than Jesus.

10. At the End of the Day, Whom Do We Know More About?

Cliffe in spinning his “10/42” source slogan probably did not realize what a wasp’s hive he had stumbled upon. His argument raised an important question: how much can we historically know about Jesus versus well-known figures from antiquity?

Upon investigation of the “10/42” statistic, it is clear that Habermas and Licona strained the number of authors who allegedly wrote about Jesus, including dubious references, such as Suetonius, and authors who make no direct reference to Jesus, such as Thallus. Habermas and Licona missed approximately 39 narrative accounts that mention Tiberius within 150 years of his life. When you re-crunch the numbers, the count for Tiberius versus Jesus comes out to 49/42. Furthermore, the flawed statistic had to stretch out the date range to an extreme 150 years in order to skew the numbers in favor of late Christian authors. When analyzing contemporary sources during Tiberius and Jesus’ own lifetime, 14 sources document Tiberius and a whopping 0 account for Jesus.

The total score card for contemporary written sources comes out to 14 literary, 100+ epigraphical, and ~100 papyrological for Tiberius in comparison to 0/0/0 for Jesus. When taking into account all of the available evidence over a period of 150 years, the data may be summarized as follows:

If it seems that the number of literary sources for Jesus in the furthest window of 150 years is impressive, there are two main reasons for that: 1) Christianity, in following the religious traditions of Judaism, made use of religious scripture, meaning that its followers wrote a lot of texts about its Messianic figure. But, most of those texts are theological in character and do not provide substantive, independent, or reliable historical information; 2) Jesus became an object of literary fascination, very similar to the historical Socrates, who likewise had several authors write about him in the decades following his death (even if many sources are no longer extant). Socrates was just a sculptor by profession, and yet he still had a multitude of authors write about him, and so I don’t find it miraculous if a carpenter had a similar thing happen to him.

I reiterate that the paucity of early, reliable sources for Jesus does not necessarily imply his non-existence. Tons of real, anonymous people lived in antiquity who receive no source attestation and are historically lost. Nevertheless, the scarcity of early, reliable sources does make the details of Jesus’ life obscure, embellished, and irretrievable to history. The Jesus that people believe in today, pray to, and discuss in church is a later theological fabrication, hopelessly divorced from the distant, ambiguous historical Jesus of the past.

Arguing, as Turner did, that Jesus is a more established historical figure than the emperor Tiberius is a catastrophically absurd comparison. Tiberius is attested by a mountain of evidence: multiple contemporary literary sources, countless inscriptions, dozens of papyri that date to his reign, coins bearing his face scattered throughout the Mediterranean, archaeological remains, statues modeled during his lifetime, and a retrievable chronology that can document important events in nearly every year of his life. I am sure that many of my readers after reading this blog have probably learned way more about the emperor Tiberius than they ever knew before! The mountain of evidence for Tiberius eclipses the small anthill for Jesus by a ratio that is beyond quantifying in a trivial, over-simplified slogan of the sort that apologists are fond of.

Apologetic arguments of this sort often remind me of a tabloid newspaper described in Ayn Rand’s Fountainhead:

“The Banner was permitted to strain truth, taste and credibility, but not its readers’ brain power. Its enormous headlines, glaring pictures and oversimplified text hit the senses and entered men’s consciousness without any necessity for an intermediary process of reason, like food shot through the rectum, requiring no digestion.”

The rhetorical games that apologists likewise spin in an effort to buttress belief in their religion are no different. Apologists like Cliffe tout how they are out to discuss the “reasonableness” of Christianity, but then throw out oversimplified lines like the “10/42” source slogan in the hope that nobody will check their data. When analyzed, the kind of arguments apologists use in ancient history are no more reliable than the 9/11 conspiracy theories are in the field of structural engineering or monster questing is in biology. People are free to believe in Christianity on the basis of faith, but pretending that this faith is rooted in historical evidence is a pernicious illusion spread by disingenuous apologetic salesmen. Correcting these misconceptions is part of the service that I seek to provide as a genuine enthusiast for ancient history.

-Matthew Ferguson

[Since writing this article I have written a sequel, in which I discuss what *I do think* historians can say with good probability about the historical Jesus, based on the sources above. In this second article I expose how most of the sources listed for Jesus in the 10/42 apologetic are either sparse or legendary, and provide little reliable information for reconstructing the life of Jesus. Nevertheless, a few of the sources have limited historical value, and I provide a summary of what they can tell us here.]

thank you

Pingback: The Four Facts of the Resurrection (Aren’t). | Roll to Disbelieve

I don’t use this term (probably the first time), but if anything is a “slam-dunk”, this is. Loved it! Enjoyable read. I don’t mind also adding that the smile on my face includes thinking of Licona’s embarrassment. He seems like a nice guy, but he can be really rude and condescending too. I only hope he will bring it up in a debate and someone having read this uses it against him.

The biggest victory of this article, in my opinion, is simply that people without academic training in ancient history can see how arguments like this are so terribly flawed. Apologists put out so many exaggerated claims about Jesus, and yet their audience very rarely has the background knowledge to assess their validity. Add this to the fact that serious scholars in academia don’t often bother with apologetics (most don’t regard it seriously), and what happens is that a bunch of spurious claims circle around the internet, such as the 10/42 apologetic, which never get refuted by serious scholars, and yet come to be believed in by lay audiences. It is simply a train wreck of public misinformation. So, I wrote this article to clean up that mess and to expose those who caused it.

Licona has admitted to the mistake, so I don’t think that he will be bringing it up in a debate. I don’t personally relish any embarrassment that was caused in his case (I have nothing personally against the guy, even after having a formal debate with his son-in-law). However, in the case of Cliffe Knechtle, I was rather glad that he was exposed. Cliffe is a charlatan who specifically targets lay audiences with claims like this, knowing that freshmen between classes will never have the background to call him on it. And, even when someone comes along who does, his film crew edits his videos to always make it look like he is the “winner.” I’ve written another post exposing Cliffe’s dishonest and selective film editing.

That said, the Latin title of this site, adversusapologetica, means “against apologetics,” rather than “against apologists” (which in Latin would be adversusapologeticos). Having to expose individual apologists is only a necessary evil. Nothing about what I do is personal. Rather, I want flawed apologetic arguments to be exposed, so that people can learn instead what serious scholars have to say about ancient history and the historical Jesus. Step one of that is dispelling the myth that we know more about Jesus than anyone from antiquity. That, as my 10/42 refutation shows, is certainly not the case, and the very fact that there has been multiple quests for the historical Jesus in Biblical Studies by itself demonstrates how obscure and historically problematic a figure Jesus really is.

Pingback: Stefan Gustavssons ”Skeptikerns guide till Jesus”, del 6, Tiberius | Jesus granskad

Just found this today. Very well done, and thank you.

This is awesome! I remember my highschool science textbook made a similar argument (yes, SCIENCE textbook) about how there was more historical evidence for Jesus than some Roman Emperor. At the time, I thought it was a stretch of belief, but I accepted it as I usually did back then. As time went on, I decided that was almost certainly garbage, but I didn’t have the historical background or training to be able to articulate why (I am working on a PhD in physics, not history). So, thanks for clearing that ancient myth up for me. I feel better now!

And one of these days, I’m going to find a used copy of that old science textbook of mine and review it chapter by chapter, because damn!

I’m glad you found the article! I put out such information for people in your exact situation, especially considering how widespread apologetic misinformation appears to be.

If you ever find the name of your old “science” textbook, and if you can find the page number and check whether this claim was specifically made in comparison to the Roman emperor Tiberius, then please let me know! I would be glad to include such a textbook on the (long) list at the top of this article cataloging of all the apologetic sources that have circulated this ridiculously bad misinformation.

I am truly astonished at how much evangelical Christians get away with abusing the education system in this country. It’s bad enough that faith-based universities with doctrinal statements affirming Biblical inerrancy, the doctrine of Hell, etc. are granted academic accreditation. But then some of the trash they publish in their “textbooks” is academically so subpar that I have to wonder if faith-based education should be considered “education” at all.

Occasionally, apologists will ask me why I spend more time targeting apologists and not mythicists, considering that I disagree with both of their historical arguments (for the record, I do plan to write on mythicism down the road, but right now I have other research/publishing priorities).

First, mythicists are only arguing for a historical hypothesis that I think is less probable than the historical Jesus existing. They are not trying to use ancient historical evidence to prove paranormal claims, which is a much, *much* greater abuse of the historical method than anything done by mythicists.

But secondly, apologetics has contaminated the education system in this country far more than mythicism ever has (if it has at all). The fact that you even read that in a “science” textbook shows just how much Christian agendas are targeting children and young adults. I don’t know if there are any elementary or high school textbooks discussing mythicism, and yet there are a ton pounding Christian propaganda into the heads of children. Having grown up within such a Christian “school,” I personally find it to be an egregious abuse of the education system. That is why, as someone who is now a Ph.D. student in real (i.e. secular) academia, I work to correct such propaganda. Correcting such misinformation helps to preserve academic integrity against the assault of apologetic agendas, which are primarily being driven out of the non-academic desire to convert people (even as children) to an ancient religion.

I am almost certain that this was the book http://www.amazon.com/Exploring-Creation-With-General-Science/dp/1932012060/ref=cm_cr_pr_product_top although it might have been one of the others in that series since I used Apologia’s General Science, Physical Science, Biology, Chemistry, and Physics 1 and 2 textbooks through Junior High and High School. I believe it was the General Science one that had an entire chapter devoted to “proof” of the Bible’s infallibility which is probably where the reference to the roman emperor was. The curriculum also had a very prominent anti-environmentalism slant, which I think bothers me more than the Creationism bullshit. I had always been a nature-lover as a child and it pisses me off that this curriculum used lies and political nonsense to poison me against common-sense environmental protections that I would otherwise have been very passionate about when I was young.

It’s a bit of a shame, because I remember really enjoying those text books. They were written in a very accessible, conversational style and, if you wrote to the author and asked a question, he would always write you back with an answer which was pretty cool. It was also quite necessary for me since I was homeschooled and the mom that was “teaching” a science class for some of us homeschooled kids didn’t actually know jack shit about most science (she had a degree in Pharmacology that she hadn’t used in many years, so I guess that qualified her to teach Physics to highschoolers? Except not?) So I often ended up having to explain the concepts to both the teacher and the class and, if I had any questions myself, I could be guaranteed that she wouldn’t know the answer. So I would email the textbook author and explain what he said to the class the next week. So I guess I can appreciate Dr. Wile for helping inspire my interest in Physics which has now carried me all the way to PhD land, even if his books were also full of bullshit.

Unfortunately, Amazon does not have a preview of either edition of the book. I am still considering buying one of the 1-cent copies of the 1st edition… maybe as a Christmas present to myself? I am not usually in the habit of splurging for things I don’t need, but it’s only shipping. If I do I’ll be sure to let you know if the emperor was Tiberius!

I grew up using the ACE (Accelerated Christian Education) curriculum in my private school, which I used up to the 5th grade before transferring into the public school system. It was a highly abysmal curriculum. Going from that to the public school system was like having my eyes opened out of a fantasy land towards how the real world actually works (granted that the public school system that I was in wasn’t very good either). One of the funniest things that I remember the ACE textbooks had were a series of moral cartoons scattered throughout the chapters, featuring different student characters facing different Christian dilemmas. I recall a comic of one kid being tempted by the kid next door to go fishing with his dad on a Sunday. But, the protagonist rebuked his friend for not resting on God’s holy day and turned him down. What rubbish. I can confidently say that, before I entered the public school system and left this “Christian” curriculum, what I was taught before was not real education.

It sounds like your science textbook was a bit better, and it’s good that Dr. Wile would respond and answer your questions. But that does not excuse the misinformation and clear propaganda in the curriculum. It is absolutely inexcusable for high school students to be taught biblical inerrancy in a science textbook (something that is entirely non-academic and solely concerned with church dogma), and the anti-environmentalism slant also tells me that the book was trying to drive right-wing, conservative agendas as well. That kind of extraneous filler is, IMO, inappropriate in an educational setting. Even if such a textbook has an engaging curriculum about science and gets students interested, it still includes propaganda and non-academic portions that about grinding a dogmatic axe and indoctrinating impressionable children.

But, I don’t know your situation as well as mine. For my part, literally nothing that I experienced in the Christian education system encouraged me to learn, be curious, or to critically think at all. All I was taught was to regurgitate Christian dogma and to be a naive, humble, and non-questioning follower, until the rapture came. The fact that I was taught such nonsense as an impressionable kid before the age of 10, and that it was not considered child abuse, simply amazes me. I literally had adults poisoning my mind as a child, simply to pound an ancient religion into my head and to compel me to convert, without any concern for me as an individual, nor any respect for the concept of education at all.

Aaah ACE curriculum. I suppose you are familiar with Jonny Scaramanga then, the guys doing the admirable work of exposing ACE for the drivel that it is and even legally challenging some of their schools for false advertising. That “curriculum” seems like truly near the bottom of the barrel in terms of misinformation and obnoxious moralizing.

I think it was fortunate for me that I did not have a comprehensive Christian curriculum like ACE. Math was untouched by religion, writing and literature were either secular curricula or at least contained little dogma. History was sometimes Christian but sometimes it was not. The only subjects that were consistently Christian curricula were Science and Sex Ed (hah if you can call it that). Furthermore, we went through a good bit of effort to find texts that were advanced and well-written. As such, when I entered college, I did not feel that I was academically underprepared.

The main problem with my form of schooling was the isolation and fear-mongering that were designed, as you said, to indoctrinate me in a religion. You hit the nail on the head when you said that there is no concern for the child as an individual when it comes to this sort of thing. The important thing is to make them complicit with your religious code. Their individuality is a THREAT to this. That’s why we didn’t have a TV, didn’t listen to music, were terrified of anything that had not been pre-approved by our parents, were told that everything in “the World” was the devil, until eventually I became the jail keeper to my own cell. I was too afraid of what was “out there” to even ask questions or investigate anymore. I would stop reading books halfway through and put them back if I got scared that there might be sex in it somewhere. I would not look up answers to my own questions if I was not sure that I was “allowed” to know them. I was wracked with guilt for years (not kidding) because I watched the care bears at a doctor’s office and it had not been pre-approved by my parents so I was scared I had watched something bad. The funny thing is, I think I restricted myself much, much more than my parents had even intended to restrict me. But that’s what that sort of isolation and fear-mongering will do to you. It will kill your own ability to question and seek and, in my case, I didn’t even realize it. Of course, I still had a natural curiosity and drive, but I only applied that to “safe” things. My mind was too poisoned against anything else.

Fortunately, you and I both got to move on to more education. It still took me years in college to finally break down a lot of the mental barriers I had built over the course of 18 years at home. But here we are. The only reason I would not classify my family’s actions as child abuse is that my experience was a very happy one, at the time. I don’t suppose that excuses it, but I have a hard time thinking back to how happy my younger years were and considering it child abuse, even though my parents were setting me up for a world of hurt when I actually had to grow up years later. I suppose each of us will see it differently.

Sorry that I’m taking up your blog feed, but it is always encouraging to me to find another person who “gets it” with this sort of mind-bending, religious indoctrination bullshit… especially someone who “gets it” without having to also respond by claiming that religion is the root of all evil and should be eradicated, etc etc. If you’re okay with still rambling away on this feed, I’d love if you could tell me a bit about what you used to believe about the rapture (since you mentioned it above) and how that affected you. And at any rate, thanks for putting up with my rambling.

Hey Galacticexplorer,

I have posted my reply to another article, which discusses my religious upbringing and deconversion experience. Rambling is totally fine, but I am going to move it out of this particular article, since this conversation has strayed a bit beyond the scope of the 10/42 apologetic. My reply can be found here:

https://adversusapologetica.wordpress.com/2013/01/03/why-am-i-not-convinced/comment-page-1/#comment-3215

Hi, Matthew.

First, thank you for an outstanding resource here. I’m embarrassed to admit I didn’t know about Κέλσος until yesterday, and it’s easily one of the most fascinating sites I’ve come across. Professional, erudite, readable–simply well done.

Second, I see that “Did Jesus ever exist?” is still up at CARM’s website, apparently unmodified, even though the author whose work it summarized largely retracted his analysis almost two years ago. CARM appears to be allowing misinformation to stand, which would strike me as poor form, to say the least. Am I missing something?

Hey Lex Lata,

I’m glad that you found the blog!

Indeed, Matt Slick’s CARM archive still has the webpage up that cites the 10/42 apologetic. This is surprising, as you note, because they cite apologist Mike Licona to back up the claim, and yet Licona has acknowledged the factual errors in the argument and retracted it. I do know that CARM has been informed of the error, at least on Youtube, because someone brought up the correct number in the comments:

My personal hunch for why they haven’t taken it down is because there simply is no reverse gear for many (not all) apologists. Atheists are the bad guys who are always wrong. Christians are fighting on the side of “Truth” and are always right (at least the fraction of evangelicals that they consider to be “true Christians,” who share their doctrines and beliefs; Slick also goes after “heretical” Christians).

So, even if they are wrong, they can’t retract it. That would mean that I was right, and I am an atheist, so I can’t be right. But, you can’t post comments on the webpage, and most people who read CARM probably won’t visit my site, so they can get away with it.

Interesting enough, I got emailed by a girl a while back who was trying to set up an online debate between me and Slick. I got back to her and said that I would be willing to have one (if it fit into my graduate schedule), but she never responded. Too bad. It would have been interesting to see us debate each other. Two Matts, with very different views, debating and all…

This comment includes quotes from the blog article at the time that I originally read it in early April 2015.

Dating the Death of Jesus (from main point #9):

// In contrast, with Tiberius we have reliable historical sources that furnish not only accurate years, but even specific days!//

#9 in this blog is misleading (especially here in the quote above) and arguably shows that Ferguson did not have a sound knowledge of the evidence concerning dating Jesus’ lifetime when writing this article originally. We have good reason to believe that we know the day that Jesus died (through identifying the lunar eclipse connected with the passover week in which He died and through reconciling John and the synoptics).

http://www.asa3.org/ASA/PSCF/1985/JASA3-85Humphreys.html

But other argumentation has been put forth as well that leads to the same date.

http://www.ncregister.com/blog/jimmy-akin/when-precisely-did-jesus-die-the-year-month-day-and-hour-revealed

*Note: Please do not construe this comment as implying that I am necessarily agreeing with the hours of death and eclipse. However, I have used Stellarium software and confirmed that a lunar eclipse did occur on the day in question in 33 C.E.

Concerning the birth of Jesus:

//Jesus’ chronology at best still furnishes this brief and sketchy estimate:

Chronology of Jesus:

4BCE – 7CE: Jesus is born

29CE: Jesus begins his ministry

30CE – 33CE: Jesus is crucified//

Luke 2:2 translation errors (i.e., “first [while]” should be “before”) should be taken into account here when considering the year that Jesus was born. When coupled with what we know about when Herod the Great died, this eliminates all dates in the “C.E.” range from being even possible as a year for the birth of Jesus. So what we have is arguably a year of birth between roughly 4 B.C.E. and the end of 1 B.C.E.

Nevertheless, on the whole, Ferguson has demonstrated here what he set out to do, demonstrating that we have excellent evidence for the historicity of Tiberius, as would be expected from a political chief executive who ruled a large empire for several years and interacted with other officials on a regular or somewhat regular basis, and in a culture which often marked dates according to the reign dates of political rulers (as Ferguson himself noted in the article).

But really, why should we expect early epigraphical or numismatic evidence for Jesus? That I do not believe is even a justified comparison to take up (especially if one were to argue Mythicism).

In the end, Christians can actually still take some degree of comfort in what Ferguson has demonstrated here, since the detail “Tiberius” in the Gospel of Luke is basically vindicated as being historical and, perhaps more importantly in this case, any makers of study Bibles and commentaries now have plenty of references from which to cite abundant evidence of Tiberius in history, and all from one blog post.

Just in case Ferguson is wondering, the Christian Apologetics community has basically moved beyond this issue of the 10/42 apologetic. (If websites still have it on there, I do not know why. I cannot recall it coming up even once within the apologetics circles I am familiar with. However, Christian apologists are now almost constantly dealing with Mythicist claims, so I’m not surprised that a Tiberius-Jesus comparison attempt appeared.)

Dear Mr. Kendall,

I am well aware that there have been multiple speculative attempts throughout history to identify a specific day, month, and year of Jesus’ death. None have been accepted by any consensus of modern scholars studying the historical Jesus. In fact, I was being rather generous in this article by saying that Jesus’ death may have dated to 29-33 CE. Minimally, scholars only agree that Jesus was probably crucified when Pontius Pilate was prefect of Judea, c. 26-36 CE.